AWO A New Look At ADVOCACY AND INFLUENCE IN WASHINGTON

"In the wars currently being fought over laws and regulations in Washington, the weapons of advocacy aren't always traditional." In the old days one could argue that in the years before muchneeded reforms were instituted, a well-connected lobbyist who was adept at entertaining could count on at least certain votes being cast as the lobbyist requested. But numerous reforms later, much of that has changed. No doubt there is still real value in an informational chat with a member of Congress over a friendly cocktail. And there is still much to be said for the access, not necessarily the votes, that an intelligently placed political contribution can gain. Yet in the wars currently being fought over laws and regulations in Washington, the weapons of advocacy aren't always traditional.

The inland and coastal domestic shallow-draft transportation industry, in fact much of the marine industry, is fighting for its very survival on a number of fronts in Washington. Among other issues in Congress, we are battling against the threat of new and disastrous user charges, and fighting to preserve the Jones Act, the foundation of our competitive position.

At the same time, we are trying to convince the Interstate Commerce Commission, the White House, and the Congress, that if railroads are permitted to gobble up barge lines, everybody except the railroads will be the big losers.

There are critical issues facing us today, and their outcome could drastically alter the face of our industry.

Educating and informing the decisionmakers in Washington, with the purpose of influencing them on behalf of a special interest, requires careful planning and innovative action. Our industry—any industry—can ill afford a lack of knowledge on how to advocate an issue, or the inability to act and act appropriately when the time comes.

One of the newest issue advocacy techniques, and one of the most successful, is to generate a large groundswell of "grassroots" support or opposition for a legislator's position on an issue, usually in the form of thousands of letters, postcards and phone calls arriving both in his Washington and home district offices a day or two prior to a key vote.

Before the vote on President Reagan's tax cut a few years back, a Congressman told me "Dammit, I'm a Democrat! I'm against this tax cut and I thought my district was against it. But I've got sixteen huge boxes of mail sitting in my office telling me to vote for this thing and the phone hasn't stopped ringing since last week. What should I do?" I stood with him on the Capitol steps as he flipped a coin in the air, watched it land, and then walked into the House Chamber to vote for the tax cut.

But the letters, postcards, telegrams, mailgrams, visits and phone calls of any grassroots campaign do not materialize spontaneously in a legislator's office. Such an effort requires careful planning, preparation and distribution of quality materials. Participants in grassroots efforts must be educated on the issues, often by their employer who is kept informed through a trade association. Alliances must be formed and in place among many—often diverse—interests.

Coalitions for action must be created that extend beyond the traditional trade association. In fact, the more diverse the basis of supporters or critics, the more the cause benefits in a Congressman's eyes, as long as the groups are all saying the same thing, in the right way, at the right time. For truly effective grassroots campaigning, substantial numbers must be involved, and careful monitoring of the issue at hand is required in Washington to determine exactly the right moment to mobilize. A good working knowledge of the grassroots process is essential to any group or industry wishing to influence a decision or advocate an important issue.

Members of Congress are aware of grassroots advocacy. They understand how it works and what it represents. They expect it, and they respond to it. Some industries have found, to their horror, that failure to understand the grassroots process can be deadly.

Think for a moment about mounting a defense against attempts to weaken or repeal the Jones Act. Think of the potential a solid and unified grassroots base, made up of marine interests—inland, coastal, ocean-going, lake carriers, small and large shipyards, associations, management, labor, et. al.—could exercise in Washington.

Another essential and less traditional weapon in the issue advocacy business is the media. What most people, including politicians, know about our industry is limited to what they read in newspapers and magazines, hear on the radio, or see on television. Barges, towboats and tugboats, locks and dams, ports and harbors are not all that visible to the general public in daily life. Every few years, along comes a network news story about some allegedly wasteful "Pork Barrel" water project. We watch as the Congressman who advocates such a project feels the heat of questioning on national television, and that's the end of it. The water project, useful or not, will forever bear that distasteful moniker, and future projects can expect the same. Yet our industry can no longer afford to be ignored or misrepresented in the media, and at the same time we need to turn the media's power of persuasion to our own advantage.

As veteran CBS newsman Daniel Schorr told a recent seminar in San Francisco: "In this mass communication society, if you don't exist in the media, for all practical purposes you don't exist." How can our industry effectively use the media as an advocacy tool on Capitol Hill? For one thing, frequent news coverage of an issue in a Congressman's hometown paper will generate letters from his constituents, will influence a newspaper's editorial bias, and will keep the issue visible in the public's mind. If a Congressman reads an editorial in his local paper about the number of jobs our industry creates in his district, he's going to pay attention. It is our job as advocates to make sure the editorial appears, and then to make sure the Congressman reads it. For example, at AWO when a pro-industry news story appears in a local media outlet, whether it's placed by us or not, we send it along with a letter to the Congressman in whose district paper the story ran.

So far, this small but effective program has been highly successful.

Congressmen read and pay attention to their local media very carefully. The local media is their free source of hometown publicity, advertising their political accomplishments and activities to potential voters when things are going well, and pulling them down with criticism and negative editorials when they don't. The local voters in New London, Connecticut or Greenville, Mississippi for example, don't look to the New York Times or Washington Post for their Congressional voting advice.

They read the local papers, watch the local television and listen to the local radio.

Generating a large number of quality local news stories on a particular industry issue can lead to news and editorial coverage by larger metropolitan daily papers.

If properly managed and channeled, the issue will be picked up by television and radio and by the wire services and the networks.

Politicians, who must out of necessity track the elusive animal called public opinion, will be carefully watching, and reading, and polling.

If the heightened news coverage can be combined with a welltimed and coordinated groundswell of grassroots action in support of our issues, no legislator can ignore it. How could he?

On many of our most critical fronts, being recognized by the media and being able to mobilize and voice our opinions will mean the difference between failure or success for our industry—between raising the decisionmaker's consciousness, or just plain whimpering alone in the dark, unnoticed.

Read AWO A New Look At ADVOCACY AND INFLUENCE IN WASHINGTON in Pdf, Flash or Html5 edition of April 1984 Maritime Reporter

Other stories from April 1984 issue

Content

- Ames And O'Donnell Named Regional Directors For Maritime Administration page: 4

- Saint John Shipbuilding Upgrades Its CAD/CAM For Big Frigate Program page: 5

- C h e v r o n Selects Elinca System For 5 Ships — L i t e r a t u r e A v a i l a b le page: 5

- Transamerica Delaval Ends Its Technical Assistance Agreement With IMO AB page: 6

- Lykes Sign Letters O f Intent To Build Six C o n t a i n e r s h i ps page: 6

- B r o g a n A n d Sundaresan P r o m o t e d At MTL page: 6

- Bestobell Mobrey Promotes Houba And Bowerman To Sales Executive Posts page: 7

- Successful T r a n s p o r t Of Biggest-Ever D e c k Structure C o m p l e t e d By N e p t u n / NC page: 7

- N a v y Seeks Comments On I m p r o v i n g Pump Specifications page: 7

- Tokyo Marine Services Is Active Worldwide — Color Brochure Available page: 8

- Richard Faber Promoted To Marine/Military Sales Manager At Aeroquip page: 8

- N a v y Awards $822 M i l l i o n To Ingalls For Construction O f LHD-1 Assault Ship page: 8

- Washburn & Doughty Announces Signing Of Three Vessel Contracts page: 9

- N e w Division Formed At G e n e r a l Electric H e a d ed By W . J . C i m o n e t ti page: 9

- Board Approves Spin-off Of Sea-Land Service To Reynolds Shareholders page: 10

- Thomas Patterson Named President-General Manager Of Coastal Iron Works page: 10

- Desco M a r i n e Delivers Its First Boats Built O f Steel page: 10

- C y b e r n e t I n t r o d u c e s N ew V H F - F M R a d i o t e l e p h o ne — L i t e r a t u r e A v a i l a b le page: 10

- NKK Super Semi-Submersible Rig Designed For D e e p Sea O p e r a t i o ns page: 10

- St. Augustine Trawlers Delivers 600-Passenger Ferry For Mexico page: 11

- Joint S N A M E / C I M E M e e t i n g Discusses Heavy Lifts And Drydock O p e r a t i o ns page: 11

- Caterpillar Announces New Marine Diesel Engine Application Guidelines page: 12

- Transfer Vessel Coal M o n i t o r One Christened In N e w Orleans page: 12

- T a m p a S h i p y a r d s A w a r ds B a b c o c k & W i l c ox $ 1 . 4 - M i l l i o n C o n t r a ct page: 12

- Los Angeles S N A M E Meeting Discusses Floating Breakwater page: 12

- NKS Heavy Forging And Facility Nears Completion Casting In Mexico page: 13

- N e l s o n N a m e d President O f M . R o s e n b l a t t & Son page: 13

- Fishing Vessel C o n f e r e n ce T o Be H e l d M a y 1 0 - 1 2 In M e l b o u r n e , F l o r i da page: 13

- Product Planning Manager Named At American Standard/Heat Transfer page: 14

- First Vessel Enters N e w Floating Drydock At H a l i f a x Shipyard page: 14

- John H a s t i e S t e e r i n g G e ar P a r t s / S e r v i c e A v a i l a b le In U.S. F r om J e r e d Brown page: 14

- Bell Aerospace A w a r d e d $ 1 0 2 M i l l i on To Build Six M o r e LCACs For U.S. N a v y page: 14

- Kienitz And Flahaut Promoted At Pott's Inland Waterways Division page: 15

- A.P.I. TANKER CONFERENCE page: 16

- French Named Chairman And C EO At NASSCO—Vortmann Is President page: 18

- DoD Implements Initiative For Cost Effectiveness Of Contract Requirements page: 18

- N a v y A w a r d s E-Systems $ 4 . 7 - M i l l i o n C o n t r a ct page: 18

- I o w a M a r i n e Delivers Towboat Betty Edwards To M o r r i s H a r b o r Service page: 18

- MTL Announces Promotions page: 18

- M . A . N . - B & W Diesel Introduces N e w Engine page: 19

- S i g m a A w a r d e d M SC C o n t r a c t For 4 0 Bilge O i l y W a t e r S e p a r a t o rs page: 19

- Hampton Roads S N A M E Reports O n Ship Production Committee page: 19

- Incinerator Ship Apollo One Launched At Tacoma Boatbuilding page: 20

- M o r r i s G u r a l n i ck Elects R i c h a r d s on V i c e President page: 20

- W e l d e d B e a m A d ds C u s t o m T e e S h a p es T o P r o d u c t Line page: 21

- Marathon-Built Rowan Gorilla I Now Drilling Offshore Nova Scotia page: 22

- SURVIVAL AT SEA page: 22

- Bay-Houston Appoints Four Executives page: 24

- Alden Introduces New Whip Antenna For Radiofax — Literature Available page: 24

- Marine Travelift Introduces Another New Model In Its Boat Hoist Line page: 25

- Norwinch And MTT Unveil New Shipboard Crane — Literature Available page: 25

- Tanker Owners Federation Will Study Oil Spill Clean-Up For U.S. Navy page: 27

- TeleSystems Opens Maritime Sales Offices In New York And Los Angeles page: 28

- Amot Controls Introduces New Sensing Switches — Literature Available page: 28

- Sonat Exploration Names Executive Vice President page: 29

- Drew Ameroid Unveils New Fuel Additive — Literature Available page: 29

- Thornton Named President Of Martime Capital, Inc. page: 30

- Raymond International Expands Offshore Services To U.S. West Coast page: 30

- Airco Introduces New Pulsed Welding Systems — Literature Available page: 31

- C l o w / G r e e n b e r g O f f e rs B r o c h u r e O n Bronze V a l v e s A n d Fittings page: 31

- U n i r o y a l D e l t a Fender Systems P r o t e c t Pier A n d Ships A t N O R S H I P CO page: 31

- Wynholds Company Will Provide Computer Systems For Maersk Line Ships page: 32

- Parkway Adds Improved Features To Its Ocean Jacket Buoyancy System page: 32

- Three Navy Patrol Boats Delivered By Swiftships page: 32

- T r a i l e r M a r i n e T r a n s p o rt A w a r d e d $ 7 . 7 - M i l l i on M S C C o n t r a ct page: 33

- WABCO To Market New High-Torque Air Motor — Literature Available page: 34

- Hempel's Introduces New Antifoulings — Literature Available page: 34

- RORO84 Nice, Frace _ May 9 -11 page: 34

- Navy Repair And Overhaul Market page: 36

- Burness C o r l e t t / S e a w o r t hy O f f e r Unique R O / R O / T a n k e r Design page: 36

- S e m i n a r M a r k s O p e n i ng O f W a r t s i l a O f f i c e In V a n c o u v e r , B.C., C a n a da page: 36

- X a n t h o s N a m e d Sales M a n a g e r For Renk's B e a r i n g s D i v i s i on page: 37

- Puget S o u n d S e c t i o n / A S NE H e a r s P r e s e n t a t i o n O n E x p l o s i v e B o n d i ng page: 37

- Big 1 9 8 4 M R O C a t a l og N o w A v a i l a b l e F r om R e l i a n c e Electric page: 37

- K o c h - E l l i s C o m p l e t es N e w R O / R O F a c i l i ty — L i t e r a t u r e A v a i l a b le page: 37

- A S E A STAL A n n o u n c es C o r p o r a t e N a m e C h a n ge page: 37

- I M E M e e t i n g Discusses Use Of Epoxy Resins In Ship M &R page: 38

- B u l k f l e e t I n c o r p o r a t ed C o n s o l i d a t e s Under N e w N a me page: 38

- L a r i m e r N a m e d Chief E n g i n e e r i n g P l a n n i n g/ C o n t r o l M a r i n e t t e M a r i ne page: 38

- S N A M E S t a n d a r ds A n d S p e c i f i c a t i o n Panel To M e e t M a y 1 7 - 18 page: 38

- Ba l d t I n t r o d u c e s N ew W o r k b o a t C o n n e c t i n g Link — L i t e r a t u r e A v a i l a b le page: 39

- N e w York S N A M E Hears Paper On Computer-Based Preliminary Design page: 39

- Unique Lobster Boat Miss Julie D e l i v e r e d By G l a d d i n g - H e a rn page: 40

- o d d S e a t t l e To Refit T w o C o n t a i n e r s h i ps For Lykes Bros. page: 40

- John C r a n e O f f e rs F r e e Brochure On End F a c e Shaft Seals page: 40

- Furuno Unveils Low-Cost Color Video Plotter — Literature Available page: 42

- MarAd To Host Fleet Management Conference April 25-27 In Chicago page: 42

- a c k u p S a b i n e V A r r i v es A b o a r d D a n Lifter page: 42

- G e n s t a r Uses N o v e l T e c h n i q ue T o Launch P e t r o b r a s D r i l l i n g Rig page: 42

- Spring Meeting Of Great Lakes/Great Rivers SNAME Scheduled For May 17 page: 43

- Magnetrol Offers Brochure On Electronic Liquid Level Transmitters page: 43

- Sperry Awards Sanders $10-Million Contract page: 46

- T e x a s Instruments Unveils N e w Loran C N a v i g a t or — L i t e r a t u r e A v a i l a b le page: 46

- Lord M a r i n e Fenders A re M a n u f a c t u r e d In 2 2 Sizes — L i t e r a t u r e A v a i l a b le page: 46

- Joint SNAME/ASNE/MTS Meeting Hears Paper On Offshore Platforms page: 47

- ASNE Day '84 page: 48

- T r i m b l e N a v i g a t i o n I n t r o d u c es The M o d e l 3 0 0 L O R A N C o m p u t er — L i t e r a t u r e A v a i l a b le page: 51

- V a l m e t ' s N e w A u t o m a t i on System O r d e r e d For T wo Product C a r r i e r s At H y u n d ai page: 51

- Propellers '84 Scheduled For May 15-16 At Cavalier Hotel In Virginia Beach page: 64

- AWO A New Look At ADVOCACY AND INFLUENCE IN WASHINGTON page: 67

- Lingaas Named Senior VP For Cruise Operations At Holland America Line page: 69

- AIMS Endorses New Marine Firefighting Training Program page: 70

- Promotions Announced At Marine Transport Lines page: 70

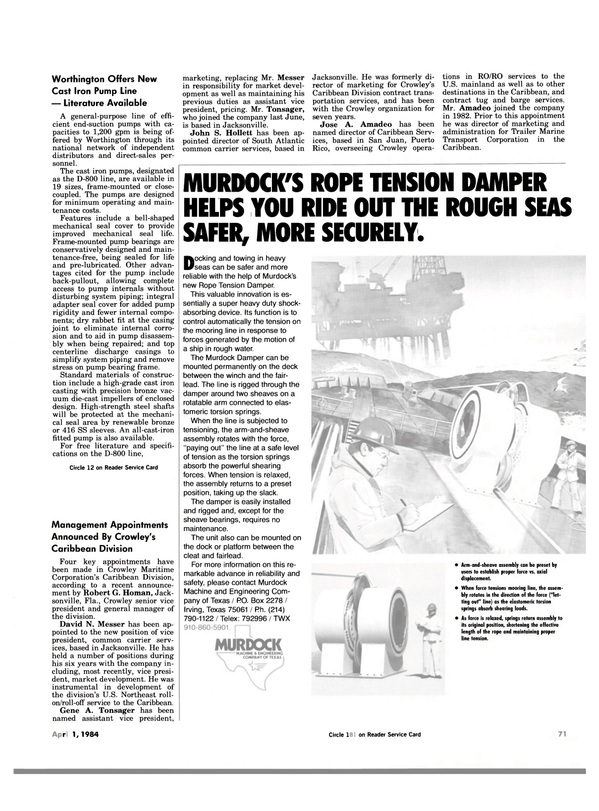

- Worthington Offers New Cast Iron Pump Line — Literature Available page: 71

- Management Appointments Announced By Crowley's Caribbean Division page: 71

- OTC 84 page: 72

- Elinca Systems To Be Installed On Five Tankers Of Chevron Shipping Fleet page: 81

- Philadelphia Resins Offers New Bulletin On Its Wire Rope Socketing System page: 81

- New Lighting Systems Catalog Now Available From Rig-A-Lite Company page: 82

- FMC Introduces Two New Crawler Cranes And Heavy Lift Attachments page: 82

- NATIONAL MARITIME SHOW page: 84

- Free Bulletin Describes Complete Line Of Kohlenberg Airhorns page: 87

- McDermott Delivers Two Caterpillar-Powered Supply Vessels To Tidewater page: 88

- New Anti-Corrosion Paint Pigments Unveiled By BP page: 89

- Westinghouse Secures U.S. Patent On Self-Protecting Sensing Cell Electrodes — Literature Available page: 89

- Tuneable Hull Plate Reduces Propeller-Induced Noise/Vibration page: 93

- Tracor Marine Awarded $6-Million Contract To Convert AT&T Cable Ship page: 94

- Nationwide Boiler Awarded $1.8-Million Navy Contract To Upgrade Steam Plants page: 95

- Full-Color Worthington Brochure Covers Specs Of Redesigned Pumps page: 95

- MSC Awards Biospherics Contract For 40 Oilarms — Option For 40 More page: 96

- Meeting Of SNAME Great Lakes/ Great Rivers Section Discusses Fuel Additives And Hull Springing page: 98

- Drew Ameroid5 Marine Introduces Four Additions To Product Line page: 98

- Chugoku Introduces New Antifouling Hull Coatings — Literature Available page: 107